Diversity and inclusion is a term that is everywhere at the moment. In job descriptions, annual reports, corporate training programs, performance objectives. The list goes on.

It has also become a single collective term. You don’t find one without the other. But have you thought about what the individual words mean? And what they mean for you?

Perhaps you have a general idea of what diversity and inclusion are, and know you should have a better understanding. Maybe you were too embarrassed to ask. If so, you’re in the right place.

Starting with the basics, we’ll explore:

- What diversity and inclusion mean

- Your legal obligations

- And a simple example of determining a diversity target

What is diversity

The word diversity means a range of different things. But a word without context isn’t much use at all. In social terms, diversity is about recognising that we’re all different in some way.

These differences range from the more obvious, such as ethnicity, gender, physical abilities and age (the latest medical breakthroughs notwithstanding), to less obvious things such as one’s religious beliefs, sexual orientation, educational qualifications, socio-economic background and mental health.

What is inclusion?

While diversity and inclusion are complementary terms, they are also distinct. Diversity is about recognising and acknowledging differences, whereas inclusion goes further by saying that these differences not only exist but are beneficial.

For example, a diverse group of people will likely have many different experiences and perspectives. When they are part of a team, their different points of view can be used to understand a given problem better and come up with novel solutions.

Conversely, a group of similar people would have less collective experiences and perspectives to draw upon. When faced with the same problem, this more homogeneous team would be more limited in their understanding of the issue, which may affect their resultant solutions.

The benefits of the team’s diversity will depend on the nature of the group and problem. If the problem is to design a new smartphone, it stands to reason that a team of diverse experts would produce a better product than a team only comprising electronic engineers.

In the workplace, inclusion is about promoting and valuing the different backgrounds and contributions of the individual members of the workforce and enabling a diverse range of people to work together efficiently.

Underpinning both of these concepts is equality. Not only do we acknowledge each of our differences, but everyone should be respected and appreciated for them and treated equally.

What are the legal requirements?

While many organisations promote diversity and inclusion, it is not an explicit legal requirement. Instead, through the Equality Act 2010, the law in the UK aims to ensure that people are treated equally in the workplace and covers what employers and employees need to do to make their workplaces a fair environment.The legislation also lists ‘protected characteristics’, which prohibits people from being mistreated for reasons of:

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- RaceReligion and belief

- Sex

- Sexual orientation

How diverse should a workplace be?

So, where to begin? Well, unhelpfully, it depends. On things like your location, your company and the types of jobs you have.

As an example, if you have a team based in London, it would seem reasonable to aim for a gender split of your employees that is representative of London, and possibly the surrounding areas from which people commute, rather than the UK as a whole. Similarly, you may aim for an ethnic split using the same sample population.

Alternatively, you may operate in a specialist sector limited by the availability of qualified candidates. In this situation, it may be more practical to aim to have a team representative of the available workforce. Nevertheless, this method is not without its challenges, particularly for roles that do not require formal qualifications. For it is much easier to demonstrate there is an unequal supply of practising cardiac surgeons than people who could potentially join a sales team.

To better illustrate the point I’ve used the 2011 UK census data for London to build up a basic understanding of Londoners and the London workforce (on census day at least).

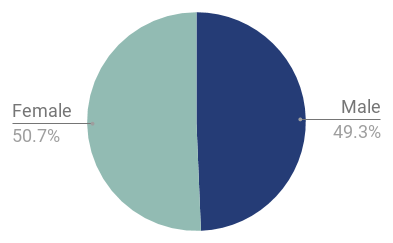

London’s Genger Split

On census day, 27 March 2011, the population of London was 8,173, 941. There were only two gender options available, and slightly more people identified as women.

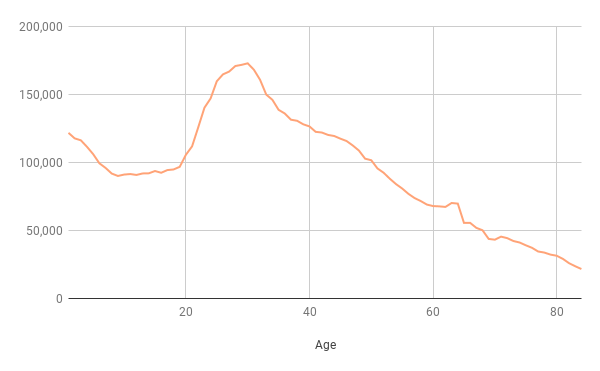

London’s Age Range

As can be seen below in chart 2, there is a somewhat distinct peak in the proportion of the London population at, or around the age of 30, followed by a steady decline. Furthermore, there were noticeably more children under the age of 5 compared to those between the ages of 8 and 14.

A significant portion of London is either too young to work, or have reached retirement age, so only a sub-segment of the population is relevant for a workplace analysis.

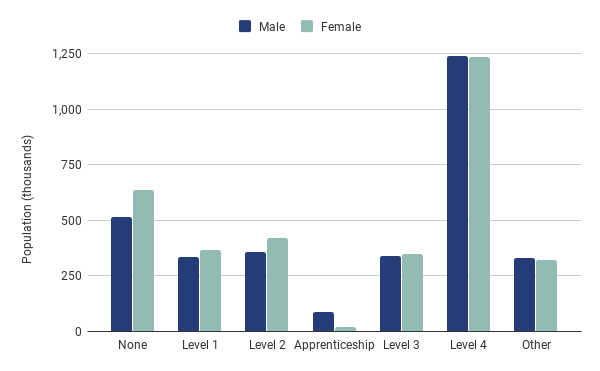

London’s Highest Levels of Qualification

Due to the increasing complexity of the economy and workplace, it is also essential to know how qualified the population is. The census asked people for their highest level of qualification achieved and segregated it into:

- Level 1: 1-4 GCSEs or equivalent

- Level 2: 5 GCSEs or equivalent

- Level 3: 2 or more A levels or equivalent

- Level 4: Bachelor degree or equivalent, or higher

- Apprenticeships

- Other: Vocational/work-related qualifications, or foreign qualifications (level unknown)

Given that those 15 and below would not have had the chance to complete their GCSEs, qualifications were analysed using the population of London 16 and over. Overall there were 6.55 million people 16 and over, which is split by qualification and gender in chart 3 below.

One should note that the above split will be in flux as people sampled continue their education, which is particularly true for the younger participants, as a 17-year-old may have yet to complete their A-levels at the time of the census, but has since gone on to complete a bachelor degree.

Chart 3 illustrates that aside from apprenticeships there is not a lot of difference between the qualifications of men and women, although women are slightly more likely to have either no qualifications or GCSEs (levels 1 and 2).

While this is a good start, London is a modern, multicultural society, and limiting our review to gender would ignore another critical factor in the diversity of the city: ethnicity.

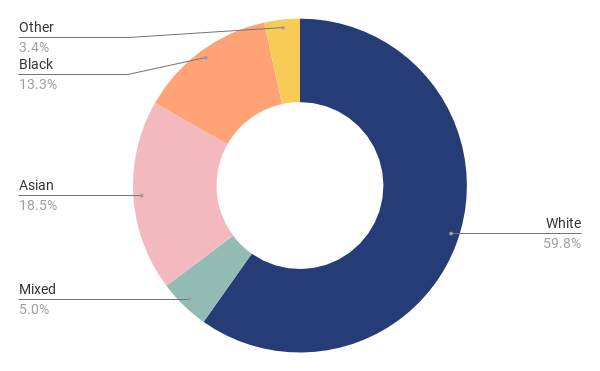

London’s Ethnic Diversity

Included in the census were many ethnic categories, which were grouped as follows:

- White - British, Irish, Gypsy or Irish Traveller, Other White

- Mixed - White and Black Caribbean, White and Black African, White and Asian, Other Mixed

- Asian - Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese, Other Asian

- Black - African, Caribbean, Other Black

- Other - Arab, any other ethnic group

The split of the total population of London by the five main ethnic groups is presented below in chart 4.

London was predominantly white at the time of the census, with all white ethnic groups making up almost 60% of the entire population. This data is for ethnic background only and does not include information on country of birth. British people will fall within all of the ethnicities, mainly by birth, but also by naturalisation.

As for our analysis of gender, in the context of diversity in the workplace, it is also helpful to understand the qualifications of each ethnic group.

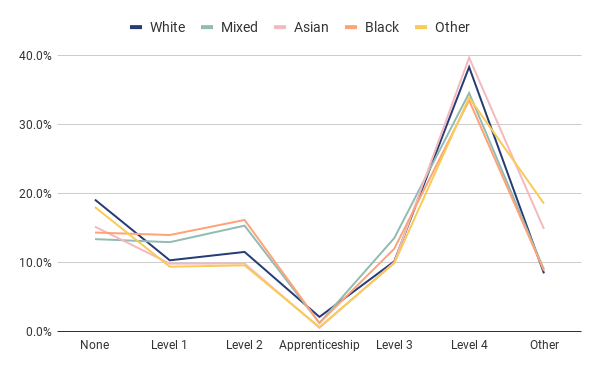

Given there are apparent differences in the number of people in each ethnic group (see chart 4 above), a proportionate approach was used for comparing the qualifications held by each group (chart 5).

The overall trends in chart 5 are similar for each ethnic group. Within the differences seen, white people are more likely to have no qualifications, while black and mixed people are most likely to have GCSEs and A levels (levels 1, 2 and 3, the latter to a smaller degree). Asian people have the highest proportion of their population to have completed a bachelor degree or higher, closely followed by white people, and the other three ethnic groups on a similar percentage, only slightly below the other two.

The most significant difference in qualification levels was in vocational or foreign qualifications (‘Other’), which ranged from 8.4 to 18.5% of the population of white and other ethnicities respectively. It’s unclear why this is the case. One guess would be that as it was the least defined category, it was more open to interpretation by the respondent.

What conclusions can be made?

Although a high-level analysis the findings are useful for developing workplace diversity targets in London:

- The population of London is relatively even along gender lines.

- In 2011 the largest proportion of the population was at or around 30 (currently 37 or 38).

- Men and women are similarly qualified, with only a few small differences.

- Furthermore, people of different ethnic backgrounds have achieved broadly similar levels of qualifications, with the most substantial differences being in GCSE and vocational qualifications.

So, in simplistic terms, given that the population of London should be relatively evenly qualified, regardless of gender and ethnicity, it should be possible to have a workforce that is diverse and representative of the community as a whole.