Your colleague David is hiring. His manager has approved the budget, HR is on board, and everything is in order. But David’s brow is furrowed. Turning to you he asks, “Do I hire for diversity or the best candidate?”

How do you answer him? Objectively, what is the right answer? Are the two mutually exclusive, or can the diverse candidate also be the best one?

Diversity and hiring don’t need to be an existential crisis. It’s simple. From research at the team, executive and board level, diverse teams and companies perform better. So, all things being equal between the candidates, promoting diversity is your best choice.

However, there is a catch. Diversity can be uncomfortable. It’ll make you question yourself. You’ll work harder. But you’ll be more successful as a result.

The effect of diversity

The effect of diversityWhen putting together a team it’s logical to start by reviewing what you’re trying to achieve and then find the people with the necessary skills and knowledge. The variety and depth of the skills and knowledge required will depend on the nature and scope of the task. For example, a company wanting to develop a smartphone would assemble a team with a broad range of expertise, covering areas such as electronics, product design, software, telecommunication networks, marketing, logistics, procurement and supply chain.

It seems self-evident that a variety of experience would be required to launch a smartphone successfully. What isn’t clear is whether who those experts are will also impact on the outcome and its success. Would the performance of a team of white men be equal to, better or worse than an equally qualified team of varying gender, ethnicities, cultures and other traits?

The added dimension of points of view

Consider the smartphone our hypothetical team is developing. What does the user want and expect from a smartphone? When and how will they use it? What features do they want, and what are they willing to pay for them?

Having people with more points of view, experiences and opinions will help the team to better empathise with their customers when designing the phone. For instance, how a married male engineer without children uses the phone will differ from a male engineer with teenage children or a single female engineer. Even physical differences can be useful. Perhaps if a few more people with below average sized hands were involved in the design of the phablet, it would be a little easier to use.

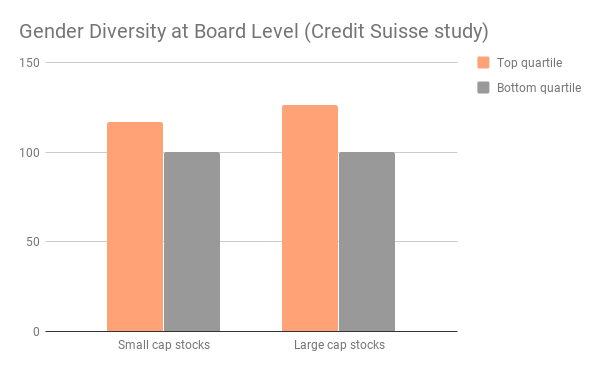

This view appears to be supported by the financial results of companies with higher diversity at the executive and board level. Using share price as a proxy for performance, a Credit Suisse study of 2360 global companies found that between 2005 and 2011 companies with at least one woman on the board outperformed their peers by:

- 17% for small-cap stocks; and

- 26% for large cap.

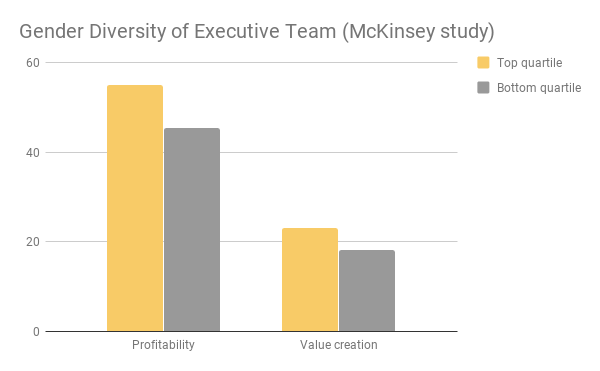

Similarly, in a 2017 review of over 1000 companies in 12 countries, McKinsey found that the companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on their executive team were:

- 21% more likely to experience above-average profitability than companies in the bottom quartile; and

- 27% more likely to outperform the bottom quartile on long-term value creation (measured by economic profit margin).

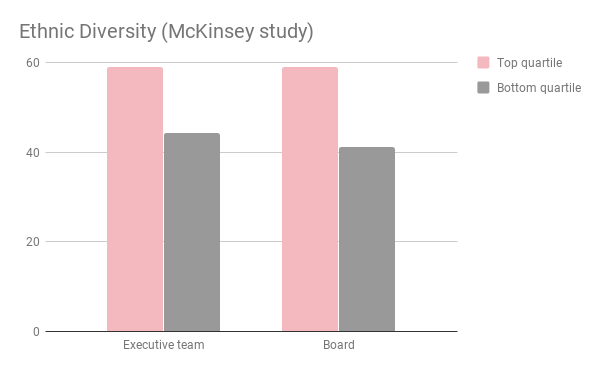

When expanding their assessment to include a higher ethnic mix and cultural composition, the results of companies in the top quartile were even more pronounced:

- 33% more likely to experience above-average profitability than companies in the bottom quartile for the diversity of the executive team; and

- 43% more likely to have above-average profitability when there is greater ethnic diversity on the board.

Overall, McKinsey calculated the financial cost of being in the bottom quartile of both gender and ethnic and cultural composition was a likely underperformance of 29% relative to their peers.

While both reports found that diversity was correlated with better financial performance, they did not prove that diversity was the cause of the increase. There was not a clear link showing diversity led to the improved performance, and that the companies wouldn’t have achieved the same results regardless of the diversity of the board and executive team.

Nevertheless, is diversity more than the sum of its parts? Can it improve the performance of the team even without bringing new information to the mix?

The uncomfortable truth about diversity

Several studies have aimed to explore not what new or different information diverse people bring to teams, but what effect diversity has when there is the same information available:

-

Phillips, Northcraft and Neale gave homogeneous teams of three white members, and teams with one outsider (two white and one non-white member) a problem to solve, and measured the teams’ approach and accuracy. All groups had common information but needed to share some clues that they each possessed. The study eliminated the effects of gender by making the groups either all male or all female.

-

Samuel Sommers ran mock trials using real juries composing six white jurors or four white and two black jurors. The jurors knew they were part of a study, but were unaware of the aim of the study.

-

Loyd, Wang, Phillips and Lount aligned teams along political affiliations (republican and democrat) and asked them to prepare to reach an agreement with someone with a differing opinion. Half of the participants were told the person would be of the same political party while telling others they would be of the opposing party.

The findings were consistent: even when teams have the same information, the diverse groups had better results. And the reason for the overachievement was changes in the way the team members interacted, prepared and worked together. However, it was not easy. Participants often reported being more uncomfortable, that the interactions were challenging, perceptions of interpersonal conflict were higher, and that they were less confident in their results (despite being right more often) than when they were in homogeneous groups.

In the small groups of Phillips et al., where the task required sharing of information to succeed, the teams with racial diversity significantly outperformed the teams with none. This was found to be due to a belief held by the homogeneous groups that they all had the same information and shared the same consensus. As they all held different clues, they consequently did not efficiently process all the information, which limited their creativity and performance.

Similarly, in the mock trials, the diverse juries were more thorough in considering the facts, made fewer errors recalling the relevant information, and displayed a greater openness to discussing the role of race in the case. These changes did not happen because the black jurors had any new information on the case, but rather because the white jurors changed their behaviour in the presence of black jurors. They were more open-minded and diligent.

This improved performance was not limited to differences of race. In the study of political affiliations, when a Democrat had to convince another Democrat with a different point of view to agree with them, they prepared less for the discussion than when a Republican held the contrary view. The same was true for Republicans. Expecting to be confronted with a different viewpoint and set of beliefs prompted the participants to work harder.

Get comfortable with discomfort

Diversity improves performance in two fundamental ways. Firstly, different people come packaged with differing perspectives, beliefs and experiences that can enrich the collective knowledge of the team. Secondly, it prompts homogeneous groups to change their expectations of a comfortable consensus and to anticipate differences of opinions and perspective. Consequently, they work harder, both cognitively and socially. It’s challenging and unlikely to be enjoyable, but it can lead to more creativity and better outcomes.

So, coming back to our melodramatic colleague David, we can tell him to relax and hire the best candidate. Just that when trying to determine who that is, he should be aware of and embrace the discomfort of interviewing and working with someone different. And rest assured that it can lead to better results for both him and his team.